Fantastic Four #1: A Beginning

Let’s talk about Fantastic Four #1, the comic that kicked off the Marvel Age of Comics. There’s no argument about its importance as a milestone in comics history, but when you put all that aside, it is one weird comic. It’s full of odd moments, contradictions, and storytelling choices that don’t quite add up. Most of us grew up with this issue as part of the backdrop of comics history, but imagine for a moment that you’re seeing it for the first time on the newsstand in November of 1961.

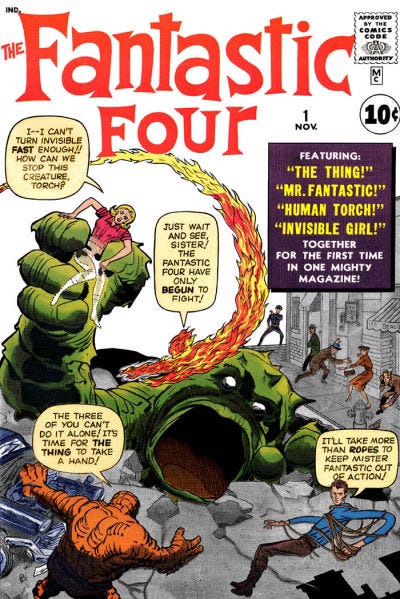

We’ll start with the cover. The scene, drawn by artist Jack Kirby, depicts a big, horrible green monster bursting up through a city street. In its right hand he clutches a blond woman who says, “I -- I can’t turn invisible fast enough!! How can we stop this creature, Torch?” A flaming figure flies toward her and answers, “Just wait and see, sister! The Fantastic Four have only begun to fight!” In the bottom left corner of the cover, a burly, scaly, orange figure shoves aside a car, completely wrecking it, and says, “The three of you can’t do it alone! It’s time for the Thing to take a hand!” In the bottom right corner, a strangely thin, almost rubbery figure lies on the street and fights to free himself from some ropes, saying, “It’ll take more than ropes to keep Mister Fantastic out of action!”

This scene does not occur in the comic book. That’s not unheard of—covers depicting moments not quite like those in the actual story cropped up now and then before, but this was different. It raises a number of questions, like: How would turning invisible help the blond woman free herself? Who tied up the skinny guy? And why is the orange guy casually destroying a car?

Here’s what the cover does tell us: The background art on this image is sparse, but it’s clear that the scene is set on a city street. We know this because there are sidewalks and stores with awnings. Five background figures watch the unfolding chaos, one a police officer. A caption names the characters, indicating that the flaming guy is the Human Torch, so when the blond—who, per that caption, must be the Invisible Girl—calls him “Torch,” we get clued into their family relationship, as well as a touch of informality. (Would a member of the Justice League of America at that time have referred to Green Lantern as merely “Lantern”? It’s a hypothetical question, but based on JLA stories of the era, it seems unlikely.)

On top of that, the word balloons tell us, the viewers, their story. They are a team, and they all want to get in on the action—with the notable exception of the Invisible Girl, whose immediate need is to escape the monster’s clutches, as though he were King Kong and she Fay Wray.

The word balloons don’t feel strange to us as we look at that cover decades later, but, as an example, when the Justice League of America made their debut early in 1960 in The Brave and the Bold #28, that cover featured a single caption describing the team as “the world’s greatest heroes,” and zero word balloons. Readers at the time probably knew who many of them were, but Martian Manhunter was relatively obscure, and no one thought to introduce him or any of the others by name.

Then there’s the series’ logo. It’s upper and lower case, bouncy and fun, and evocative of the early space-race. (The logo for the 1965 TV series “Lost in Space” has a similar feel.) Others have said it before, but it has a playfulness about it. A circus-like feel. Future Marvel comics would play up the drama with their logos—see, for example, the Incredible Hulk or the Amazing Spider-Man. Among the early Marvel comics, only The Avengers has a logo with a look like this—another comic, you may note, featuring a circus of characters.

Now, on to the story. Fantastic Four #1 begins as the shadowy figure of Mister Fantastic stands in the window of a tall building and uses a flare gun to summon his teammates to him, saying, “It is the first time I have I have found it necessary to give the signal. I pray it will be the last!” We cut to the other three as they drop what they’re doing to join their leader; Susan Storm was visiting with a “society friend” for tea, before freaking out a cabby by catching a ride while still invisible. In a clothing store, the big orange guy angrily gives up trying to buy clothes that will fit his huge frame, then crashes into the street and escapes the police by diving into the sewer. He comes back up to street level just in time for a car to crash into him; all the while he blames everyone but himself for his troubles, calling those around him fools and cowards. Meanwhile, young hot-rod enthusiast Johnny, who we learn is the Human Torch, turns to flame and melts the car he and a friend were working on, then encounters fighter pilots called out to respond to him—a mysterious flaming figure flying over the city. He melts the planes just as the elastic arms of Mister Fantastic reach into frame to catch a missile launched from one of the planes. Those arms toss the missile into the sea and then catch Johnny himself, whose flames have been exhausted. This all happens in eight frenetic pages.

These characters cause chaos and destruction across the city as they rush to join their leader, and suffer no repercussions for their actions. What follows is a quick telling of the team’s origin story: Susan Storm pressures Ben Grimm to pilot Dr. Reed Richards’ new spacecraft despite Ben’s concerns about cosmic rays. After takeoff they are showered with cosmic rays (which make a “tac tac tac” noise) as Ben predicted. They then crash back to earth and learn that they have gained strange new powers. After demonstrating their newfound abilities, they pledge to become a team and help mankind.

Flashing back to the present, we learn what their inaugural mission is: Some unknown force is causing atomic plants across the globe to disappear into the ground. Reed’s data pinpoints the source of the trouble on…wait for it…Monster Island.

After some requisite grumbling from Ben Grimm, the team jets off to Monster Island, where Reed and Johnny fall through a collapsing hole in the ground and are captured by the Moleman. While Ben and Susan try to rescue them, with Ben griping every step of the way, the hideous Moleman—he could be uncle to The Simpsons’ Hans Moleman—reveals his pathetic backstory, in which he is rejected by women (“What? Me go out with you? Don’t make me laugh!”), prospective employers (“I know you’re qualified, but you can’t work here! You’d scare our other employees away!), and potential friends (“Hey, is that your face, or are you wearin’ a mask? Haw haw!”).

By the story’s end, we’ve seen ten giant monsters, more or less, all of which could have come from any one of Marvel’s contemporaneous mystery titles like Journey into Mystery or Tales of Suspense. Series like these were mostly focused on monster stories that featured plucky heroes saving the planet with their wits. Those monsters would soon be on their way out as Marvel introduced more super-heroes to their lineup.

What we don’t see in this issue are costumed super-heroes. It’s been speculated that Marvel’s editor, Stan Lee, and publisher, Martin Goodman, were cautious about introducing super-heroes so as not to attract the attention of National Periodical Publications, publishers of Superman, the Justice League of America, and Batman. National had set some of the terms under which Marvel secured a badly needed deal with a distributor that had ties to National.

It’s not hard to imagine that artist Jack Kirby was also acting out of caution. From 1957 through 1959, Kirby had been drawing comics for National. That relationship ended when Kirby and his editor, Jack Schiff, had a falling out over the newspaper comic strip Sky Masters of the Space Force; Schiff took Kirby to court over monies he felt were due to him; one of the results was Kirby having to leave National and return to Marvel. This was just after the 1950s comic-book witch hunt that nearly wiped out the field entire, which left artists like Kirby with very few options for employment.

Kirby’s work for National included the first twelve tales of the Challengers of the Unknown, a quartet of male adventurers who narrowly escaped death in a plane crash on their way to take part in a radio show. They decided to form a team, uniformed in purple outfits with white belts not unlike the FF’s own uniforms, which would debut in issue #3 of their series.

Fantastic Four takes that basic setup and ups the stakes. The FF ride a rocket ship, determined to beat the commies in the space race, making their motivation geo-political rather than entertainment. Unlike the Challengers of the Unknown, the new team includes a woman, and the foursome has ties to each other; it’s noted that Susan and Reed are engaged to be married, and while it’s not fully spelled out in this issue, it’s clear that she and Reed both know Ben well. Johnny, of course, is Susan’s kid brother.

The Challengers of the Unknown was a team made up of adventurers who share circumstances, but the Fantastic Four was something more: an extended family. No matter how they bicker—and there’s a lot of that coming in the decades to come—they find their way back together. The Fantastic Four made its debut two years after two years after Kirby left National, but one can see how he would have wanted to avoid poking the bear by giving the Fantastic Four super-hero costumes, at least at the beginning.

So, what about the characters? At this point, the Human Torch may be the most fully developed of the bunch: He’s a hot-headed (get it?) hot-rodder who doesn’t want to be left out of the action when his sister and her boyfriend plan to rocket into space. His youthful enthusiasm for cars places him in high school, most likely—as do his appearance and his slightly loose grammar; he drops his Gs, as in “taggin’,” and calls Susan “sis.”

The Thing is angry at the world, a reluctant participant in the events of the story. Susan gets him to pilot Reed’s rocket ship by calling him a coward (she never apologizes). Why it was so urgent that they make their fateful flight at this time is never explained, and we never find out how much time goes by between their rocket ride and their encounter with the Moleman. When the foursome’s new powers are revealed, Ben cuts off Reed’s speech-making to grudgingly accept what seems to be his destiny: to play hero to what he sees as an ungrateful world.

Of the four, only Ben’s physical appearance has been permanently altered by exposure to cosmic rays. His transformation into a rocky, scaly, orange…thing makes him look like he belongs among the creatures of Monster Island. Earlier in the story he tries to disguise himself in an overcoat, hat, and dark glasses, all of which he dramatically bursts out of no less than three times in this story.

Ben’s dialogue through the issue shows Stan Lee working to develop his speech patterns. His first word balloon in the issue reads, “Bah! Everywhere it is the same! I live in a world too small for me!,” while his final line reads, “Can’t you even hold on to one little guy?,” aimed at Reed. The shift away from formality is noticeable, and would slide even further in stories to come.

In this inaugural story, the Thing seems to loathe Mister Fantastic for his transformation into a monster. Marvel would quickly build its identity by featuring heroes who squabbled, but this was outright hatred. Ben’s attitude would soon soften, while Reed developed a sideline in trying to cure him. His efforts would usually prove to be temporary; in those instances where they seemed permanent, Ben would be forced to sacrifice his happiness and revert to the Thing to save the others.

Reed Richards and Susan Storm contribute the least to the story. It takes some time for Lee and Kirby to figure out what to do with Susan, both in terms of her personality and her powers. Eventually they would expand those powers so that in addition to turning invisible she could also project force fields—a great power, to be sure, but what that has to do with turning invisible is anyone’s guess.

As for Reed, well, for a hero whose powers are based on stretching, he comes off in this issue as a bit of a stiff. The issue’s origin sequence tells us more about him, though. After the other three announce their heroic names, Reed says, “And I’ll call myself…Mister Fantastic!!” Incredibly, none of the others call him out on that bit of self-mythologizing, which is all the more amazing considering they haven’t called themselves the Fantastic Four at this point.

Full credits for the story, another hallmark of the Marvel Age of Comics, are missing from this issue. At a time when no comics publisher featured credits, and artists rarely signed their work, the signatures of Stan Lee and Jack Kirby appear on page one of the story, but with no credits near to their names. (In recent years this would lead to one of the great mysteries among comics historians: Who was the inker of this issue over Kirby’s pencil art? The leading contender is George Klein, today best known as the inker on Superman stories drawn by Curt Swan.) Just over a year later, Fantastic Four #9 ran these credits:

Script…Stan Lee

Art…Jack Kirby

Inking…Dick Ayers

Lettering…Art Simek

Marvel Comics credits would go through many iterations in the years to come, adding many additional and intermediary areas of responsibility, as well as jokes, snarky asides, and tricky wording designed to pave over the truth. Not too many years later, credits in the Fantastic Four would read, “A Stan Lee and Jack Kirby Production!” This was meant to assuage Kirby’s demand for credit as co-writer of the stories, but it just muddied the waters, making it harder for readers to know who did what.

Another thing missing from Fantastic Four #1? The words “Marvel Comics Group.” The cover sports a small box with the letters M and C stacked inside, but a look at the issue’s indicia (that little block of type at the bottom of the first page) lists its publisher as Canam Publishers Sales Corp. This was one of the shell companies operated by publisher Martin Goodman. Marvel Comics Group appears on the cover for the first time with issue #14, close to a year after issue #1’s debut. The word Marvel had been kicking around Goodman’s organization for decades already, though, starting in 1939 with the very first comic book Goodman published, Marvel Comics #1 (which, incidentally, introduced the original Human Torch—the one who wasn’t actually human). A tiny box with the letters “MC” appeared on covers a few months later, followed by the familiar corner box cover lock-up with the words “Marvel Comics Group” and the price of 12¢.

Despite all this, Fantastic Four #1 sets the stage for so many Marvel Comics to come. The team argues among themselves; they show off, and feel jealousy and anger. The storytelling proceeds at a breakneck pace, getting its point across not through exposition so much as blink-and-you’ll-miss-it references to things we might not have seen actually happen.

It was a beginning.

A bit in there that wasn't really followed up on -- unless someone did it much later -- is Sue's hanging out with "a society friend." Sue was set up to be a glamorous actress/model/socialite, but as developed didn't turn out to be any of those things, but instead the suburban stand-in mother figure for her younger brother, since their mother's death and their father going to jail.

She was presented as someone who got photographed a lot because she was an FF member, but not really a working model before then. She apparently daydreamed about being an actress but hadn't done any of it. And she wasn't a society figure, she was very middle class, if not working class.

But it was apparently Stan's instinct that she should be Jackie Kennedy. Interesting to think about how the FF would have developed if they'd stuck with that. Maybe they'd have been financed by Sue's money, not Reed's. Maybe she'd be in charge of their public image -- she was the one to come up with the costumes, but she could have done a whole lot more in that direction.

Instead, she was played as a helpmeet, not someone with her own career, fortune or social standing.

Solid breakdown. The thing about the cover not matching the story is intersting when you think about it as a marketing decision rather than a continuity mistake. Kirby was basically selling the concept before nailing down execution, which kinda explains why the FF felt so experimental. That detail about Ben's speech patterns evolving across one issue shows how much they were figuring it out in real time.